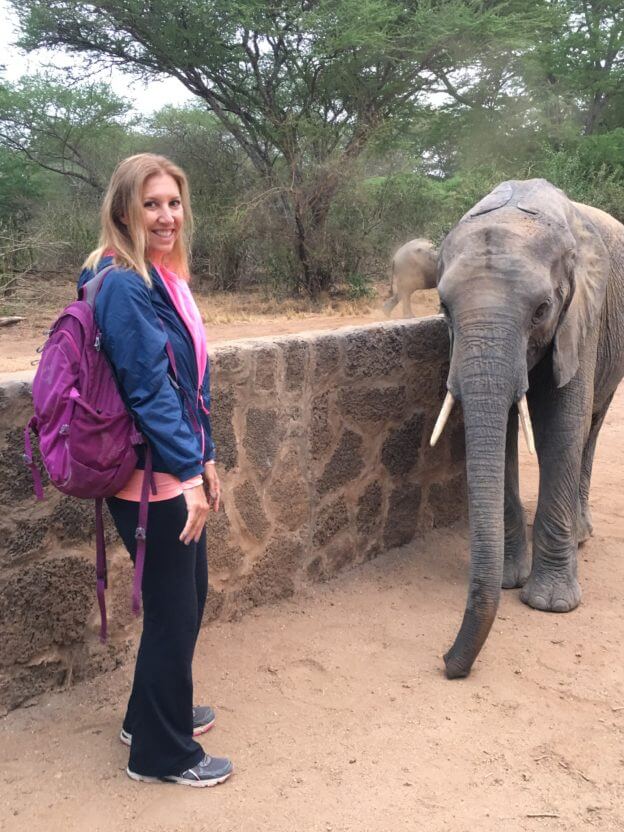

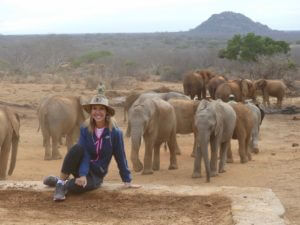

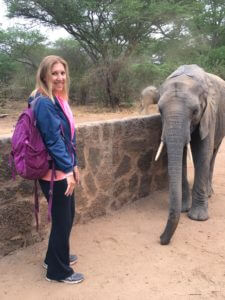

Nicole Korensky traveled to Kenya from late September to early October. She visited elephants at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust Ithumba Reintegration Unit in Tsavo National Park.

By SARAH DOOLITTLE, Four Points News

Nicole Korensky has a passion for elephants and their welfare, so much so that she just returned from her third trip to an elephant sanctuary in Kenya.

“My dream would be just to work with elephants directly, but… you don’t really have local opportunities,” said Korensky, who lives in Steiner Ranch with her husband and three children.

When she is not busy as president of the Canyon Ridge Middle School PTA, she volunteers in area schools educating students about elephant protection and preservation.

She came to love elephants as an adult after watching a documentary on TV then touring a private elephant sanctuary in Tennessee.

A “60 Minutes” episode about the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya sealed her fate and set her on her current course. The trust, created in 1977, conserves, preserves and protects wildlife. They are renowned for their orphan project, which rescues orphaned elephants and rhinos and returns them to the wild. “I was like, oh, I have to go there,” said Korensky.

Elephant nursery

That dream was realized in 2012, when Korensky’s aunt and uncle were headed to Kenya on a safari and invited her to join them.

“It was mainly a safari, but we did visit the (elephant) nursery in Nairobi,” said Korensky. “That’s where they rescue the baby elephants and bring them directly to the nursery… I was so happy.”

Elephant sanctuaries

The experience made her want to do more for elephants. In 2014, she visited two sanctuaries in Thailand, where elephants are killed for their tusks or, more frequently, used for labor, either for riding by tourists or for heavy lifting and pulling.

“It’s just horrible” she explained. “And they break them when they’re babies, so they can never go out. It’s really sad… They’re chained 24/7.”

In 2016, she returned to Nairobi, this time specifically to visit the sanctuary.

At the facility, operated by the trust, staff rehabilitate elephants and rhinos for reintroduction in the wild. But first, the animals must be raised like any human baby, “These men… they’re the elephant keepers,” Korensky explained. “They basically live with these elephants in the nursery. They sleep with them every night. Because they’re babies!”

Into the wild

“Eventually, when they think they’re ready, they just go off and join their own wild herd,” she said.

Elephants in the wild can live twice as long as those in captivity, up to 70 or 80 years, but domestication shortens their lives by limiting their natural need to walk 30-40 miles a day and to live in family herds and feed on a diverse diet.

There are stories of what the sanctuary staff call ex-orphan elephants. “They will come back, and they’ll visit the keepers because they know it’s a safe place. They’ll have babies in the wild, and they’ll bring the babies right away to show them,” she said.

Korensky was deeply impressed by the people she saw working at the sanctuary and their skill with the animals. “I kept getting choked up, because these people were just so kind and sweet.” As much as she wishes there were no need for such a place, “You’re glad to know it’s there.”

Ecosystems also suffer when elephants are absent. Elephants are what’s known as a keystone species, meaning they are essential to the overall food chain. In their absence, systems that have functioned for millenia quickly break down.

Meeting elephants

Meeting elephants in person was, for Korensky, a magical experience. “They would come up to me and… lift their trunks and then they wanted to smell me. And you have to be kind of calm… You are supposed to blow into their trunks and that’s how they scent you.”

And though she has a healthy respect for elephants — “I’m not going to lie, they scare me too.” — she was overwhelmingly moved by meeting them.

“I look at their eyes like looking into their souls. because you just see the pain that they’ve been through and your heart is just like, wow, you know,” she said. “(They)’re just so giant and majestic and I mean I’m just, I don’t know how to say it but to be in (their) presence is an honor.”

In Thailand, Korensky was amazed by the elephants’ calm despite the suffering they had experienced at the hands of humans. “We got to walk alongside the elephants. These are elephants that were rescued… (and) probably had years of abuse. So that’s another redeeming, amazing quality… I can’t see humans forgiving each other that easily, you know. After all they’ve known from humans is abuse, yet these elephants are so gentle.”

Sharing the cause

From all these experiences, Korensky said, “I kind of figured out my passion in my life. It’s elephants.”

Elephants are currently considered endangered globally. Their populations are, according to Scientific American, estimated at less than one half to one fourth of what they were at the turn of the 20th century. Humans are biggest threat to elephants. Poaching for ivory and other parts of the elephant, legal sport hunting and humans encroaching on elephants’ habitat have all taken their toll.

“Trophy (hunting) is so unnecessary in this day and age,” said Korensky. “There is no reason to kill the large species like that when they’re already under such a threat.”

Understanding elephant’s fragility has only fueled Korensky’s passion. She’s taken this passion and knowledge into local classrooms with the hope of sharing it with a younger generation.

After her initial trips to Kenya and Thailand, Korensky approached her kids’ teachers about doing a short presentation about elephants. “The kids loved it.”

The experience was so gratifying that, afterward, Korensky reached out to the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. They were able to connect her with their educational resources, created by the foundation to help spread the word about protecting elephants.

She has given presentations in a half dozen area schools in classrooms and assemblies, as well as at the Lake Travis Community Library and to area homeschoolers. Korensky estimates she has spoken to nearly a thousand students about elephants.

Korensky takes a life-size cutout of an elephant with her to every presentation. “The kids love it. Then I take their picture next to it, and it’s lots of fun.”

Students often send cards and letters after seeing the presentation, and Korensky loves seeing how students have been impacted.

“To me, I feel like it’s kind of filled that feeling of giving back to the elephants and to the world… by doing these presentations,” she explained. “This is the closest I can get to elephants besides going overseas and seeing them.”

Making a difference

Korensky’s daughter shares her passion and in 2016, the then 12-year-old spoke to the Austin city council about banning bullhooks, which are used to train and control domesticated elephants. The measure passed.

“She made such an impact because she was 12 years old, you know… So that just shows you kids can really make a difference,” she said.

Using her voice to make a difference is where Korensky sees herself making the biggest difference for elephants.

“That’s why I’ve always have a really soft heart when it comes to animals because I just feel like they don’t have a voice,” Korensky said. “So the only voice they have would be someone like me or someone that cares enough to talk about them and help them.”

Nicole Korensky with an orphan Quanza, an elephant that lost her entire family to poaching. She now lives at Umani Springs with the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust.

Nicole Korensky with elephant orphans from Umani Springs in Kibwezi Forest with the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust.